Seahawks were kings

Early teams were fun to watch, classy

Source: The News Tribune

September 1, 2000

By Dave Boling

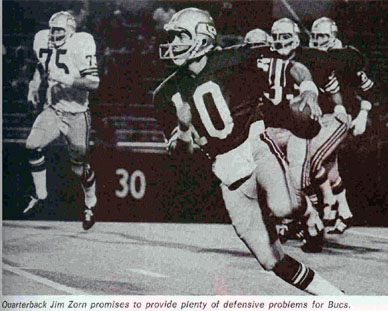

Seven rookies started on that team ... fatal youth for any NFL squad. The one at quarterback, Jim Zorn, threw 27 interceptions and just 12 touchdowns (QB rating of 49.4). In every other city, he'd have been driven from town, but he was adored by these new fans. As was his beneficent sidekick, receiver Steve Largent.The average salary for those Seahawks in 1976 was under $40,000, Nordstrom said.

And the fans got their money's worth.

Zorn went on to be the offensive rookie of the year for the NFC - the conference in which the team played that first season. And defensive lineman Steve Niehaus was the conference's defensive rookie of the year.

The Seahawks were so hastily formed before the 1976 opener, there were five players on the field who had practiced with the team only twice.

In his first postgame interview, quarterback Jim Zorn once referred to a teammate as "No. 44." That was the best he could do; he didn't know his name.

"I'm disappointed.

"There's a lot of emotion right now," says Jim Zorn, the team's first quarterback of reaction to Behring's attempt to move the club to Los Angeles. "I'm not crying or anything. But I'm disappointed. Not just for Seattle, but for every other city losing a team."

"I had everything I owned shoved in my VW."

"A friend of mine drove me up, towing my Volkswagen behind us," says Zorn, a free agent out of Cal Poly Pomona. "I had everything I owned shoved in my VW. And I still haven't gone back."

"Hmmm. Not very much."

This is what quarterback Jim Zorn remembers about the Seahawks' first game as a member of the AFC West, against the Denver Broncos: "Hmmm. Not very much. I know we lost because we started that '77 season 0-4."

The low point of his career

"When I got benched in that '83 season. Not being released in '85, but being benched, because I was so used to being the starter."

Regarding the redesign of the helmets in 2002

"I don't know if these new helmets will hit any harder or look any more intimidating." They probably won't. In fact, the one thing people say when encountering the new color is, "My, what a pretty blue."

The Seattle Seahawks

by James R. Rothaus, 1980

"This may sound corny, but the thing that's exciting about the Seahawks is that they really try hard. Each season, that's what will be going on. We'll be trying hard -- trying our best for the fans."

Norm Evans' Seahawk Report

Vol. 4, No. 13

Sept.27 – October 3, 1982

Zorn, meantime, continues to deny that he has asked Seahawks’ management to trade him. “No, I

haven’t,” insisted Zorn. “Besides, I don’t think they (the Seahawks) can afford to trade me. See what happened to Dave? What if they didn’t have me to turn to?”

Jim Hoping to be Zorn Again

Inside the Seahawks

Vol 1, No 4

August 29th-September 4th, 1986

By David Takami

Jim Zorn has been through enough seasons in the National Football League not to panic.Although his is waiting for a tryout with another team, he is not angst-ridden about the possibility that his football career might be near its end.

"I'm going on the premise that I could get a call," says Zorn, a 10-year veteran. "But I'm not waiting by the phone and answering on the first ring, and saying, 'Which team is it?'"

Offer or no offer, "I won't be surprised either way," he says.

Last month Zorn was let go by the Green Bay Packers, for whom he appeared in 13 games last season, including five starts. It was an up-and-down season for the Packers, who finished 8-8. Zorn played most of the season as a back-up QB to Lynn Dickey, throwing 56 of 123 passes for 794 yards.

Despite his one-year stint with the Packers, Zorn can't help but be a Seahawk fan.

"I watch the team with great interest," he says.

The Pride of Z-eattle

By Jim Natal

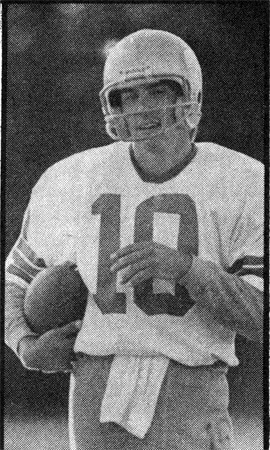

It is eight o'clock in the morning. Jim Zorn is standing in the Seattle Seahawks' weight room catching his breath between lifts. The plain light gray of his practice t-shirt and shorts contrasts with the dark, sweat-stained wide leather support belt he is wearing. Along the walls behind him are various Nautilus weight machines, looking menacingly medieval in the light of the early morning, like inventions copied from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Except for a battered radio that Zorn has tuned softly to an easy listening station, it is silent in the room.On first meeting, three things are instantly apparent about Zorn. He seems bigger than his program size of 6 foot 2 inches, 200 pounds. He doesn't photograph especially well; he is better looking in person that he is in most photos. And the naïve, boyish image, the John Denver-ish personality (kind of Rocky Mountain without the high) has been greatly exaggerated.

Zorn, at 25, is young, yes, to handle the burgeoning responsibility of his position and the public acclaim that goes along with it, but he is by no means the shy, wide-eyed innocent the media have often made him out to be. He is soft-spoken and deeply religious, yet, having grown up in the 1960s and 1970s, he knows what is going on. He seems to have his priorities in order.

So far, he has managed his success well. He owns a house in Redmond, just east of the Seahawks' headquarters outside Seattle. His only extravagance has been the purchase of a beautifully restored white 1955 Bentley fastback that he keeps in his garage and shows off with a mixture of price and embarrassment. But he also still has the yellow Volkswagen convertible he drove in college.

Suddenly Zorn exhales sharply and bends to the 175-pound barbell at his feet. Grunting with each repetition, he completes his workout. Training camp is still nearly a month away but this year he knows he will be hard-pressed for his job. Besides backups Steve Myer and Sam Adkins, there will be three first-year quarterbacks to contend with. No one ever said it was going to be easy. And it certainly hasn't been.

By all rights, Jim Zorn should not be playing professional football. Not that he doesn't have the ability. He does. He's proven that on the field in his first two seasons with the Seahawks, leading them to a 5-9 record in 1977, the best in NFL history for a second-year expansion team. No, it's more that he wasn't sure about playing football almost up to the time he got to the pros. For one thing, he didn't have the early commitment seemingly from grade school on that characterizes so many pro football players. In some ways, his starting for the Seahawks is as much a matter of circumstance as was his sitting on the bench during his years at Gahr High School in Cerritos, California.

"When I was younger," he explains, "I had bad experiences with sports; not getting picked to play, always getting picked last. I was small and skinny," he adds, grinning at the irony of his now well-muscled frame, "and I cried a lot."

"When I got to high school, I decided I wouldn't play sports…thought I'd be a ladies' man." He laughs. "I had this friend who actually talked me into going out for cross country. That really wore me out. The same guy later talked me into going out for football. He wanted to be a receiver and I thought I'd either be a receiver or a defensive back.

"Then one day in practice, the coach came over to me and asked me if I wouldn't mind playing quarterback until they brought some guy over from the varsity. I liked the idea of playing quarterback, of being a leader. The older guy took over from me soon after that. It wasn't until my senior year that I got into a game as a starter. We won.

"Oh yeah, I did get one shot in my junior year. You know how at the end of the game they put all the wienies in? I was in for one series and I broke my wrist. And that took care of that."

After high school, Zorn attended Cerritos Community College for two years, then transferred to Cal Poly (Pomona) for his junior and senior years. At Cal Poly, he began to develop his football skills. In fact, the major problem Zorn's coaches had with him was trying to keep him alive. In addition to being a strong passer, Zorn was a strong runner and on keeper plays and sprint outs he often refused to run out of bounds to avoid getting hit.

"In college," he says, "it wasn't until my junior year that I had a good season." Zorn is being modest; "great" season would be more accurate. In 1973, running Cerritos's sprint-out defense, Zorn completed 138 of 337 passes for 2,367 yards and 16 touchdowns. He earned Little All-America and little all-coast honors and was named Southern California College Division player of the year. He didn't do as well in his senior year, due to a number of coaching changes. Yet Zorn still finished his two-year career at Cal Poly with 5,314 yards in total offense (1,164 rushing), setting 10 school records.

"Until after my junior season," he says, "I still didn't care much about football. I never really thought much about playing pro ball until my senior year."

But then came the 1975 NFL draft and disappointment. Despite his spectacular play, Zorn was not chosen.

Zorn unbuckles the support belt and drops it to the floor. The thick leather and heavy brass makes a sound like a saddle falling off a fence. Zorn lied on the floor and tucks his feet under a bar of one of the nautilus machines. He does a fast set of twenty bent-legs, twisting sit-ups. Getting to his feet, he goes out into the parking lot and begins to run up the long, steep driveway that leads out onto Lake Washington Boulevard.

It is a beautiful morning, sunny and clear, the rising warmth in the still air hinting at the heat to come later in the day. Zorn sets an easy, relaxed pace for the three-mile run down the highway to the town of Kirkland and back.

Returning to the weight room after his run, Zorn is greeted by Seahawks trainer Bruce Scott. "How do you feel?" Scott asks. Scott, a pleasant, intensely professional man, is the entant terrible of Seattle's training room. His toughness, especially with players who don't take care of themselves, is legendary with the team. So when Scott inquired about a player's health, he is usually told - in the detail he expects.

"I feel good," Zorn replies, sipping orange Gatorade from a paper cup. "Except that slight hamstring pull still feels a bit tight."

"Okay," says Scott, gesturing toward a padded training table, "lie down. I'll get you some ice."

Zorn lies on his stomach while Scott puts some ice in a plastic bag, adds some water, and seals the bag. He puts the bag on the back of Zorn's right thigh and asks, "Is that too cold?"

Zorn laughs. "Since when do you care about that? Remember that time with the tub?

Scott laughs self-consciously.

"One time Bruce told me and another player to soak our legs in an ice bath," says Zorn. "We tried it and thought our legs would freeze off. We told Bruce it was too cold. He didn't believe us, so we said, 'We'll make you a deal. We'll keep our legs in there for as long as you can keep your arm in.' Bruce rolled up his sleeve and stuck his arm in the tub. After about ten seconds he pulls his arm out. 'It's too cold,' he says."

Scott shrugs and re-adjusts the ice bag. "Jim doesn't give me anything to do," says the trainer. "He does it all himself."

Zorn's discouragement at being passed over in the draft was dispelled when the Dallas Cowboys called and offered him a tryout as a free agent. "The Cowboys' camp was the toughest place I had ever been," he recollects. "So much was new to me and there were all these great athletes there. I found I didn't understand football. Not really. And the pressure to perform was tremendous right away. I just decided to do the best I could."

He went all-out every day. Though he found the complicated Dallas offense difficult to understand at times, his determination to succeed carried him through the training camp. He made the team - almost.

When the final cut came and went, Zorn knew he had beaten out seven other prospects to become the Cowboys' number three quarterback behind Roger Staubach and Clint Longley. He was ecstatic. But it didn't last. The Cowboys were short on running back and two days before the season opener, they got a chance to pick up veteran Preston Pearson on waivers from Pittsburgh. To make room on the 43-man roster, somebody had to go. It was Zorn.

"I was aware of what was going on with Pearson," Zorn relates, "so when the coach Landry asked me to come to his office, I knew what he wanted. He told me they had decided to go with two quarterbacks. They offered me a job in Dallas to keep me around. But I knew I could play. Landry told me he thought so, too."

Zorn was understandably depressed about being cut so late but he held no bitterness toward the Dallas club. "I learned a lot at the Dallas camp," he says. "Dan Reeves, the quarterback coach, was a real big part of it. He really encouraged me. And Roger Staubach taught me a lot, too. He taught me how to be competitive. He'd be racing me in the drills. He didn't have to race me. I was no threat to him. But he just did it. That's Roger. He really helped me out."

After leaving Dallas, Zorn returned to Southern California, where he had a brief try-out with the Rams. They were impressed with him but they didn't have space on their roster, either. So Zorn went home to Cerritos and sat out the 1975 season.

"He really felt bad," recalls his mother, Esther Zorn. "Getting cut by the Cowboys at the last minute broke his heart. He was thinking of going to Canada to play. His dad talked him out of that. He told Jim, 'Why don't you stick it out a little longer and maybe one of the American teams will pick you up.' Sure enough, Seattle did."

It was more than a coincidence that Zorn became a Seahawk. One of the first employees hired by the new Seattle franchise was director of player personnel, Dick Mansperger, who had been with Dallas in the same capacity since 1972. Mansperger remembered Zorn from the Dallas camp. When Mansperger found out Zorn was available, he quickly grabbed him for the new team.

Mansperger's memories of Zorn's talent and his instincts about the raw, young quarterback were prove accurate in 1976, the Seahawks' first year. Zorn passed for 2,571 yards, breaking both former Buffalo quarterback Dennis Shaw's 1970 rookie passing record of 2,507 yards and Fran Tarkenton's expansion team passing yardage record of 1,997 set with Minnesota in 1961. Zorn also threw for 12 touchdowns, had five 200 yard-plus days, and finished in a tie with running back Don Testerman as the club's second-leading rusher with 246 yards on 52 carries (a 4.7 yard average) and four touchdowns. Despite Seattle's 2-12 finish, he was selected as the NFC's offensive rookie of the year by the NFL Players Association.

"I think the biggest factor against Jim when he came to us was that he never had the same coach two years in a row," says Jack Patera, Seattle's head coach. "Coming to us after four years of college and a training camp with Dallas, I think made him do a bit of extra work, whereas another quarterback who had been in the system might have been more polished.

"From scouting reports and the information we had on his background, we knew he was an excellent prospect. He had the background for us to say, 'This kid could be a good quarterback.' We'd never take a free agent and say, 'This kid is going to be a star.' But he did become an almost instant success for our first preseason game."

In 1977, Zorn picked up where he had left off in his rookie year. In the preseason, he led Salina to three consecutive victories, including a 12-10 come-from-behind triumph over Oakland. "When Fred Biletnikoff walked off the field," says Zorn, "he was a little upset. He said, 'Wait'll we get you down in Oakland'."

Biletnikoff and the Raiders made good the threat later in the season, trouncing the Seahawks 44-7. The week before, however, Zorn had engineered the most brilliant performance of his career. Playing in Seattle's Kingdome against Buffalo, Zorn led the Seahawks to a 56-17 romp, hitting 11 of 23 passes for 296 yards in less than three full periods. He threw four touchdown passes and ran for a fifth score in a game that saw the Seahawks break or equal 20 individual and team records.

The Buffalo game marked Zorn's first starting appearance in four games. In a 42-10 loss to Cincinnati in the second week fo the season, he suffered a knee injury when he tackled Bengals' cornerback Lemar Parrish after an interception.

Patera believes the side line time did Zorn no harm. "It's hard for any athlete, especially a quarterback, to deal with an injury," says Patera. "Sometimes, though, it can be beneficial. I think it was beneficial to Jim."

"Nobody wants to miss four games, but in Jim's case I think we derived some value from getting him to sit back and put things in perspective. I think that the two games he spent sitting up in the booth with Jerry Rhome [the Seattle quarterback coach] and seeing how Jerry calls the game, learning the reasons behind the calls, and then seeing the calls work helped Jim. He came off his injury and ended the season having a tremendous second half."

By the end of the 1977 season, Zorn had led the wide-open Seattle offense to a second-year expansion team scoring record of 282 points. He also combined with teammates Myer and David Sims to throw an NFL team-high 23 touchdown passes (16 were Zorn's). Unfortunately, the team also led the NFL in most points allowed (272) and most touchdowns given up (43) - hence the 5-9 overall record in spite of the crackling offense.

Catching one of Zorn's passes is something akin to getting hit with a pointed rock. Waiting his turn to run a pattern in an informal passing drill Zorn had organized, defensive tackle Dennis Boyd said, "I caught one against my side yesterday. When I took my hands away, I thought the ball would stick there by itself."

Across the practice field, a maintenance man rides a lawnmower, the familiar drone of the machine making an aural backdrop to Zorn's signal calling. He is surprisingly quick in his drop and even faster on a sprint-out. He also has the exceptional ability [for a left-hander] of being able to roll right and throw accurately on the run. This speed, coupled with a quick release, kept Zorn's sack figure down to 12 in 1977.

Zorn also has a unique trio of favorite receivers, each with his own style of running a pass pattern. Coming out of the backfield, Don Testerman doesn't so much run a pass pattern as charge it. Sherman Smith, the other running back [who was a receiver in college], doesn't run either; he's so smooth he flows. As for Steve Largent, the Seahawks' leading wide receiver, Zorn has called him "a circus in himself." Zorn divided his passes almost equally between the three of them last year, Largent catching 33 passes, Testerman 31 and Smith 30.

"Jim has a good 'touch' on the ball," says Largent. "He can throw a line drive in there when he has to, but when youv'e got a play when you're wide open, he can lay it in your hands."

"I think, too, the fact that he can scramble so well is an added pressure on the defense. When he can turn a probable sack into a gainer or a touchdown, it puts pressure not only on the defensive backs, but on the defensive linemen as well."

Largent feels there is more to Zorn's success, however, than just his passing and scrambling ability. "What makes Jim a better quarterback is that he is such a hard worker. He's a competitor who always wants to improve his play. He always works hard in practice and, before the season starts, he'll do anything to get out there and throw the ball to receivers. His competitive edge pushes him and he pushes himself to the max. No one's more disappointed when he plays badly than Jim himself.

[Zorn] pulls his yellow VW into the parking lot of the health food co-op where he shops. He goes in and bags an assortment of nuts and natural food items. As he passes the produce section, his eyes light up. Zorn loves cherries and the bin of fresh organic cherries at 49 cents a pound is too much to resist. He loads up.

At the checkout counter, the cashier recognizes his name on his check. "Aren't you that football player?" she asks.

"Yes," he replies.

Blushing, the cashier says, "You appeared at the school over there not too long ago."

Zorn nods.

"You autographed my daughter's arm when you were there. I don't know why she had you sign it there. She wouldn't wash it off. We let it go a few days, but we finally made her wash it off. It was getting ridiculous."

Back in the car, Zorn opens a small carton of peach kefir and takes a drink.

Zorn shakes his head, smiling, at the thought of the little girl whose arm he autographed. Does it all seem like a game to him now that he's made it?

"Football is a game," he answers. "A complicated, strategic game. I also think of it as a job." He finishes the kefir, takes a handful of cherries, and beams that disarmingly boyish yet knowing grin. "But it's a blast. I love doing my job!"

Seahawks

by Doug Thiel

Sunrise Publishing Inc.>

No team makes it far without an outstanding quarterback. Seattle has a quarterback who throws with uncanny skill, evades defensive tacklers with deftness, and runs with determination—Jim Zorn.

Jim Zorn explained the differences which face a ball player from the time he begins playing in high school until he finally makes it as a professional. “In high school coaches tend to stress the winning attitude, let’s win as a team, let’s pull together. In college you have a scholarship and the school has an investment in you. It’s still a team and it’s still, ‘Let’s win as a team.’ But more of it has to do with your performance. In professional football it’s your living. Everything, including the coaches’ job depends on how well you do so they drive you to get the maximum out of you. They do everything to make you the best athlete that you can be. In the pros you’re representing everybody, not just friends, family, and alumni clubs. Now, I’m representing Seattle. I’m representing the state of Washington. There’s a lot more at stake in the pros than there is when you’re playing in high school or at college.”

“In high school you’ve got your studies to worry about, your girl friend, your peers, you’re not as smart, you don’t really stand the concept of the game.

“In college they expect you to understand the concept of the game. You also have to maintain a grade point average. Sometimes it’s unbelievable what coaches have to do to guys to get them to class. Because you have a scholarship you think you have a free ride, you’re a jock, and your teachers will pass you. At some colleges that is true. As long as you go to class you get a C. At Cal Poly, if you didn’t study, you were just out of it. That was good for me because they forced me to study. If I didn’t do the job, I was out.

“Finally you graduate to pro ball. There a football player is a football player. That’s what we’re getting paid for, to perform on the ball field. The coaches are paid to coach so they don’t have to recruit like they do in college. They don’t have to baby sit.”

Norm Evans' Seahawk Report

Vol. 4, No. 13

Sept.27 – October 3, 1982

Word has it that just before the New Orleans Saints traded veteran quarterback Archie Manning to the

Houston Oilers for holdout guard Leon Gray, the Oilers tried to swing a deal with the Seahawks for Jim

Zorn. According to one source, the Oilers were offering Seattle quarterback Gifford Nielsen plus a second

round draft choice this year and an undisclosed pick in 1983 for Zorn, who lost his starting job to Dave

Krieg before re-claiming it after Krieg suffered a thumb injury in the Houston game. The Seahawks

apparently were reluctant to trade Zorn and before trade talks could continue the Saints offered Manning

to the Oilers. Seattle’s reluctance in peddling Zorn stemmed from the fact it would have little insurance

at the position if he were gone.

TEAMMATE BLASTS ZORN

SYRACUSE POST-STANDARD

Monday, April 19, 1982

Veteran center Art Kuehn of the Seattle Seahawks has lashed out at

teammates Jim Zorn and Steve Largent for their stated position on a

possible National Football League players' strike next season.Zorn and Largent, the Seahawks' standout quarterback-wide receiver combination, have said publicly that they would not take part in a strike. Both Zorn and Largent are devout Christians and both have listed religious grounds for their decisions."That would hurt us (the National Football League Players Association)”, Kuehn said in a recent interview.

"I don't respect them for their stand. That's hurting the union."

Jim Hoping to Be Zorn Again

by David Takami

Inside the Seahawks, Vol. 1, No. 4, Aug 29-Sept 4, 1986

Jim Zorn has been through enough seasons in the National Football League not to panic.Although he is waiting for a tryout with another team, he is not angst-ridden about the possibilitythat his football career might be near its end.

"I'm going on the premise that I could get a call," says Zorn, a 10-year veteran. "But I'm not waiting by the phone and answering on the first ring, and saying 'Which team is it?"'

Offer or no offer, "I won't be surprised either way," he says.

Last month Zorn was let go by the Green Bay Packers, for whom he appeared in 13 games last season, including five starts. It was an up-and-down season for the Packers, who finished 8-8. Zorn played most of the season as back-up OB to Lynn Dickey, throwing 56 of 123 passes for 794 yards.

"I have been continuously working out," says Zorn, now back at his Mercer Island home. "But I haven't been throwing as much as I need to be sharp."

Really, he is not unlike many other 33-year-olds considering a career change: open to possibilities. Two weeks ago, commuters may have been surprised to hear him as guest DJ for two days on KJR's drive time morning show. Besides dealing with the pressure ofjuggling weather, traffic, news, and sports reports, Zorn, still enormously popular with Seattle fans, spoke with listeners. One of them was his twoand-a-half year old daughter.

"Dah-deel Dah-deel" screamed Sarah Zorn in her radio debut.

It wasn't Dah-dee's first experience in radio. During one off-season when he was a Seahawk, Zorn had a Saturday morning show on the Bellevue-based station KZAM.

He has been investigating other work possibilities too, one with a cellular phone business, and another with the Washington Huskies, as an assistant quarterback coach.

And Zorn would love a chance at football commentary. Like any fan he likes to watch football games on TV, but unlike the average viewer, he sees plays as a quarterback might from the sidelines.

"Some of the analyzing is (off the mark)," says Zorn. "I watch what's going on and listen for what the commentators will say. They miss a lot of things I see. I'm not polished but I think I would really do a good job."

He gave one example in the Hawks' first preseason game with Indianapolis. After a broken play, in which Gale Gilbert rolled out to his left and passed out of bounds, the announcer blamed it on John L. Williams' "rookie mistake."

Zorn saw it differently. "Gilbert ran the wrong way. The line was blocking in the other direction." Despite his one-year stint with the Packers, Zorn can't help but be a Seahawk fan.

"I watch the team with great interest," he says.