John McMakin was there!

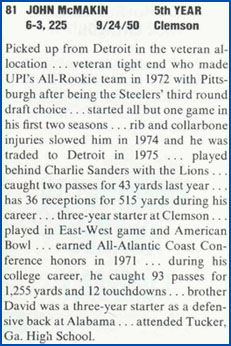

I'll bet you thought the Immaculate Reception was all about Franco Harris (who was a Seahawk for a season!), Frenchy Fuqua and Jack Tatum! Think again, Seahawks fans!! Our 76er, John McMakin was in on the play too!

Street and Smith's Pro Football 1977

When he wasn't throwing to Largent, Zorn looked for tight end Ron Howard, the ex-Seattle U. basketball player, most often. The ex-Cowboy caught 37 passes in his first role as a starting tight end. The other wide receiver, Sam McCullum, caught 32 balls. He and Largent caught four touchdown passes. The experienced subs are tight end John McMakin and wide receiver Steve Raible.

Pro Football 1976

by Larry Felser and Dave Klein

Wide receivers aren’t bad. The starters figure to be Alamad Rashad and Sam McCullum, but two rookie picks, Sherman Smith and Steve Raible, and veteran Don Clune will fight for steady work. John McMakin and Ron Howard will battle young Charles Waddell for the tight end spot.

Hawks Howard Sheds Nickname

By Gil Lyons

Despite the loss of hard-luck Charles Waddell to knee surgery, the Seahawks are strong at tight end.John McMakin was Pittsburgh’s third-round draft choice four years ago and was named on at least one all-rookie team. He started for the Steelers that season.

Arvis Darby, a rookie who was converted from wide receiver, is an excellent prospect.

Seahawks History

Source: Inside the Seahawks

Vol. 1, No. 14

November 7, 1986-November 13, 1986

By Bob Pruitt

Atlanta scored first, an 18-yard field goal, after Seattle quarterback Jim Zorn fumbled on the Seahawk 9 yard line. Then Seattle made its one "unassisted" scoring drive on the following kick-off. Sherman Smith capped the 80 yard drive by hauling in a 21 yard TD strike from Zorn. Zorn passed for another touchdown to John McMakin only seconds later, after John Leypoldt's kick-off was fumbled by Rick Byas on the Falcon 26.The third quarter began with a Seahawk drive being stalled near mid-field. Rick Engles punted the ball to the Falcon 6, where Rolland Lawrence took it in and was forced to run for his life by the exceptional Seahawk coverage. With Don Dufek immediately in his face, he retreated laterally back near the end zone where he was caught by a pursuing Dave Brown, who nailed him for the safety.

The next two Seahawk touchdowns were results of great play by the defensive secondary. The first was the Matthews' interception return for 6 points. The other was a Sherman Smith breakaway touchdown run of 53 yards following Brown's second interception.

Seahawks 30-Falcons 13

Author: Alan Adams, Class of 1967

Source: Tucker High Alumni

Category: Memories-THS Athletics

Subject: Former Football Stars

Date: 08/23/2000

I'm glad I can partially answer your question since I played varsity football with all three of the people you mentioned. I'm not sure where Jimmy Chesnut is now, but he was a great running back for the Tiger teams of the mid 60s. I played varsity ball in 1965 and 1966 with Jimmy, his older cousing Greg Chesnut, and both David McMakin and his older brother John. David did play for Alabama as a defensive back and now lives in Huntsville, Al. He was our backup QB behind Chuckie Mize (later a successful High School Coach who is now deceased). John did play pro ball as a wide receiver for both the Pittsburg Steelers and the Seattle Seahawks and did get to at least one if not two Super Bowls with Pittsburg. He retired from the Seahawks and still lives in Seattle working in the commercial fishing industry. Their parents still live in Tucker.

The house that the 'Immaculate Reception' built

Franco Harris has heard mention of a plaque

Source: Chuck Finder, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Frenchy Fuqua figures it deserves more than that -- much more than a hunk of bronze and a pithy little inscription.After all, isn't Pittsburgh the city of champions where half of the Forbes Field wall remains (where Bill Mazeroski's 1960 World Series-winning homer owns its personal commemorative spot) and where even that old home plate merits a marker in a University of Pittsburgh hallway?

So Fuqua wants similar permanence. He wants something big and bold and shrine-like when Three Rivers Stadium gets torn down and made into a parking lot 28 years to the week after its most famous freeze frame -- its signature moment in sports history.

So Fuqua wants similar permanence. He wants something big and bold and shrine-like when Three Rivers Stadium gets torn down and made into a parking lot 28 years to the week after its most famous freeze frame -- its signature moment in sports history.

He wants a sanctuary to the Immaculate Reception.

"That's holy ground," said the former Steelers fullback, the guy who collided with history, football and Oakland's Jack "They Call Me Assassin" Tatum near the game's end on Dec. 23, 1972, a day that lives in perpetuity far beyond Pittsburgh.

"No matter what happens, when they tear Three Rivers down, a monument ought to be built there," Fuqua said recently from his office at the Detroit News, where he is a circulation manager. "Even if they end up building a hockey rink there, they should put some kind of a monument to that area where the Immaculate Reception took place.

"It's not about Frenchy Fuqua or Franco Harris or Jack Tatum. The concept of that play and the turnaround our team would make after it -- that makes that turf special, and I would hate to see that ruined."

The play that took place in the then-2-year-old concrete bowl by the confluence will endure far longer than the stadium itself, scheduled to get razed hours after the Washington Redskins-Steelers finale Dec. 16.

A new, 70,000-seat stadium arises barely a few feet to the west. A new, 38,000-seat ballpark nears completion two blocks north up the Allegheny River.

The old cookie cutter is about to be turned into a parking lot, and no one is sure yet what kind of monument will be erected to commemorate the play from 28 years ago.

For of all the 2,490 Pirates games, the 255 Steelers games, the 68 high-school football playoff games, the seven AFC championship games, the two World Series, the handful of Pitt football games, the countless concerts in the round that occurred by the intersection of the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio, one instance stands above the rest.

One 17-second span of time, to be precise.

"The quintessential moment," longtime Steelers linebacker Andy Russell described it. "Everywhere I went, all over the United States and including the Bahamas, everybody knew what I was talking about," Fuqua said. "Three Rivers. They never confused it with Riverfront."

Harris recently returned from Italy with his mother, and the notion of an outdated stadium made him chortle. "Especially after coming back from seeing the Coliseum," he said, "it does make you wonder what old is."

Yeah, but Rome wasn't built in a play.

"We had so many great years there -- the Pirates and the Steelers," Harris added. "Even Pitt with some of the games they played there. A lot of great things happened during the '70s there that were incredible.

"But nowhere in my wildest dreams did I think the Immaculate Reception would get as big as it's been."

THE HISTORY

First of all, let's puncture a few myths.

Don't believe every Pittsburgher who tells you that they feasted their eyes on the Immaculate Reception, because only 50,350 were inside Three Rivers that day and the sold-out AFC divisional playoff was blacked out on local television. Congress amended that policy the next year.

"All those years after, everybody I met was at that game," former linebacker Jack Ham said. "It must have been held at the Coliseum in Los Angeles."

And don't believe anyone who says they heard the shrill voice of legendary Steelers color commentator Myron Cope on that play, because he had already left the booth for post-game interviews and stood beyond the end zone into which Harris ran.

And don't believe the Raiders' contention that it was the first use of instant replay, either.

Secondly, let's set the scene with some Steelers history to that juncture. Art Rooney's franchise had been a Litany of Losers, with capital Ls.

Thirty-one of their previous 39 seasons, the Steelers failed to compile a winning record.

With the exception of the 1939 season, featuring future Supreme Court justice Byron "Whizzer" White at back, there are few highlights to note from the era.

The Steelers had more seasons of two or fewer victories (10) than they had seasons over .500 (eight); they had as many as three coaches in one season (11-game 1941); and they had once combined with Philadelphia in 1943 and 1944 to become the Steagles, who lost and lost and lost and lost and lost and lost and lost and lost and lost and lost (all 10 games).

They had become a self-fulfilling Pittsburgh prophecy: S.O.S., for Same Old Steelers.

Chuck Noll became coach in 1969 and the next day drafted a gent named Joe Greene along with a 10th-rounder known as L.C. Greenwood. That first 1-13 season brought Terry Bradshaw and Mel Blount in the next draft.

The following 5-9 season brought a new stadium, Jack Ham, two starting offensive lineman and the rest of the Steel Curtain front four, Dwight White and Ernie Holmes.

Then in January 1972, the puzzle was closer to complete with the addition of Lydell Mitchell's blocking fullback from Penn State -- Franco Harris.

The rookie set records while rumbling to a 1,055-yard season, and the 11-3 Steelers reached the playoffs for only the third time in history.

The postseason brought John Madden's reckless Raiders to Three Rivers, and the sturdy Steelers defense used two Roy Gerela field goals to stake a 6-0 lead.

Then, with 1:13 remaining, Daryle Lamonica's replacement -- some kid named of Kenny Stabler -- got loose for a 30-yard run around left end and the visitors owned a 7-6 advantage.

SAME OLD STEELERS?

Hold onto your hats, here come the Steelers out of the huddle. It's down to one play, fourth down and 10 yards to go. . .

The ball was at the Steelers' 40-yard line. The radio voice belonged to Jack Fleming, longtime Steelers and West Virginia University play-by-play announcer. His is the voice you hear on the NFL Films footage of the play, which remains its most replayed football moment from the company's vaunted vaults.

Terry Bradshaw at the controls. Twenty-two seconds remaining. And this crowd is standing. . .

Noll called for a 66 Circle Option, with receiver Barry Pearson the intended, albeit unexpected, target on a post pattern.

Bradshaw is back and looking again. . .

Oakland defensive end Tony Cline surged and just missed the quarterback, flushing him to the right hash marks, around the Steelers 29.

Bradshaw running out of the pocket, looking for somebody to throw to. . .

Fuqua, aligned in a split backfield with Harris, circled into the Raiders' secondary and tried to get the Steelers into Gerela's range.

Fuqua picks up the story: "Life is full of 'if' -- if the pass protection hadn't have gone down, if the pass rush hadn't made him run (to Fuqua's) left, he would have hit me with a short pass, I would have run out of bounds, Gerela would have kicked the field goal, and we would have won. But everything happens for a reason."

Harris, staying in to block and confronting no one, looked back to see Bradshaw avoid a rushing Horace Jones and began to throw. Having learned at Penn State to follow the ball, Harris -- from the Steelers' 35 -- commenced running down the middle of the field.

Initially, Tatum covered Pearson on the post pattern. But Bradshaw took his eyes off the receivers, as a quarterback is wont to do when scrambling desperately.

"When I looked up again to see what I could find, the only thing I could see was Frenchy," was how Bradshaw described it a few years ago. "I was about to get hit. I unloaded it."

Fires it downfield. And there's a collision. . .

More Fuqua: "I was wide open. Tatum took off the post. As I planted for the curl, if Bradshaw throws the ball, I'm wide open. I said in my mind, 'He's coming, no doubt about it.'

"I hear footsteps. I'm thinking, 'Bradshaw, throw it.' I hear (Tatum) breathing. We're all running toward a point. I don't want him to step in front and intercept it, then run down the sideline.

"I'm hauling ass to get to a point and he's coming at the same speed to destroy whatever's coming to that same point."

RAIDERS WIN . . .

Tatum, to this day, denies that the football hit him. Which means if it struck Fuqua, then it was a pass tipped to a teammate illegally under 1972 rules.

"It doesn't really matter now," he said with a laugh recently in a radio interview.

But he clouted Fuqua at the Oakland 35, the ball sprayed elsewhere, and the self-proclaimed "Assassin" firmly believed the game was over. Raiders win.

"I didn't see Franco catch the ball," Tatum said. "I thought, 'He's sure in a hurry to get to the locker room.' "

And. . . (unintelligible). It's caught out of the air! . . .

Still more Fuqua: "I'm on the ground and look up. Jack's jumping up and down smiling. Then, while he's in the air, the smile turns to a frown.

"A lot of the doggone Oakland Raiders, when they realized Franco had the ball, they didn't know how to react. It was something you can't believe; there was doubt in everyone's mind."

The ball is picked up by Franco Harris. Harris is going for a touchdown for Pittsburgh. . .

Harris had arrived at the Oakland 42, having "jogged" there, according to covering Oakland linebacker Phil Villipiano, and the flying football came to greet his shoetops.

The rookie reached down and snagged it. He veered to his left, ran down the sideline, and only Oakland defensive back Jimmy Warren would interrupt his jaunt -- although a stiff-arm at the Oakland 10 took care of him.

Villipiano lamented years later, "If I was as lazy as Franco (jogging to that 42-yard line point), it would have been an easy catch for me because Franco was on my outside."

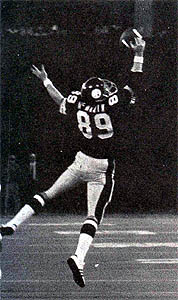

He also claimed that Steelers tight end John McMakin, a few steps behind Fuqua, then clunked the Oakland linebacker on the back of the legs after Harris' catch: "The biggest clip ever."

Harris is going. . . . Five seconds left on the clock. Franco Harris pulled in the football. I don't even know where it came from. Fuqua was in a collision. There are people in the end zone. Where did it come from?

Bradshaw, flat on his back, heard the roar of the crowd and later recounted how he thought to himself: "You really are amazing. You put that baby right in there."

By the time he arose, he knew he had heaved a game-winning touchdown pass. He just wasn't sure how. Neither were the officials.

Back-judge Adrian Burk signaled touchdown, but there was no further confirmation from officials. Referee Fred Swearingen huddled with his crew and described the meeting results later as four "I don't knows" and two "I thinks."

He went to Steelers sideline official Jim Boston -- then in charge of security and field conditions -- and asked for a nearby telephone. Boston took Swearingen into a dugout.

Art McNally, then supervising, got the call. "Two of my men say that opposing players touched the ball," Swearingen told him.

"Everything's fine then, go ahead," McNally responded. When Swearingen put the phone down, Boston asked, "What do we got?"

"We," Swearingen said, "got a touchdown."

Boy, did we. Oakland's John Madden protested that one Steeler tipped it to another in violation of the rules. All he got for his argument was the dugout telephone. He turned it into a trophy for his home.

CHANGES EVERYTHING

Long before "The Catch" or "The Drive" or "The Music City Miracle" or whatever other catchphrases folks so readily want to bestow anymore, there was this wondrous event.

A Pittsburgher named Michael Ord was in a tavern and anointed the play moments later with a nickname taken from a Christmastime Catholic holiday, and his friend Sharon Lavosky telephoned Cope at the television station where the Steelers' announcer also worked, performing commentaries.

Thus begat the Immaculate Reception.

Same Old Steelers? They lost the next week to the undefeated Miami Dolphins, though several of those Steelers still feel they should have solved the Dolphins and won the Super Bowl that year.

Rather, they had to settle with four rings over the next six years.

But they emerged from Dec. 23, 1972, as Super Steelers. The NFL team of the decade.

The play emerged from a couple of polls and one NFL Films' compilation as the league's No. 1 all-time moment.

"1972 was a magic year for us," Harris said. "Part of that magic was capped off in the playoff game with the Immaculate Reception. That was just the start of a great decade."

Fuqua has been offered six-figure sums to divulge whether the Bradshaw pass actually struck him.

"I'm never going to say anything," he said. "Something like that, you want to keep it Immaculate for all time. I like that idea. I've spoken to Franco about it. We're going to keep it Immaculate."

Harris runs into Madden on occasion. The Super Steelers played the Raiders in flag football more than a decade later and the Oakland fellows were still so incensed that several flag-footballers from both sides wound up badly injured and in need of medical attention.

"(The players and Madden) still say that was illegal -- that they should have won that game," Harris said. "No, they were not destined to win that game. No, not that one."

Chuck Finder, a Pittsburgh sports writer for the past 15 years, was raised 25 miles southwest of the city -- but still in the blacked-out television area back in 1972. A Steelers fan as a youngster, he felt the desperation of that fourth-and-10 situation with 22 seconds remaining. So much so, he picked up a telephone while listening to the radio broadcast and rang up "Dial-A-Prayer." It wasn't something little Jewish boys were supposed to do, but, after the play, he figured Higher Callings didn't care about denominations or affiliations . . . Just true belief.

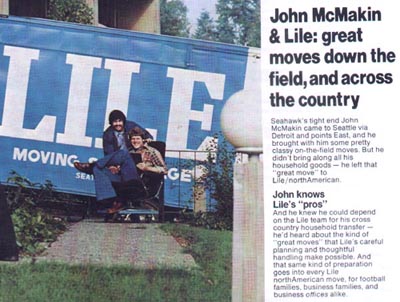

Source: NASE

Association Field Services

Thank you for your interest in our programs! We are able to customize health insurance plans specifically for you. We have a commitment to provide you high standards of service. I played in the National Football League for years with a lot of rough contact, so I know the value of good health insurance. After many years of being self-employed, my wife and I found a plan we liked with our company. Now, as an agent in Washington, I can appreciate the challenges you face in running a business and feel we can offer you some quality benefits to help fight the high cost of health care. I look forward to working with you.

The Pocket Book of Pro Football 1976

Edited by Herbert M. Furlow

Former Steeler starter John McMakin may be the best of the lot. Ron Howard is another tight end; he may try for the top job. He was on Dallas special teams. Don Clune was little used by the Giants but when given time did well; he has speed, but little experience. Sam McCullum also doubles as a kick returner. He hurt a shoulder in 1975. Raible, a rookie, hopes to break in.

Lurtsema, five others released by Seahawks

Daily News-Miner

Fairbanks, Alaska

Wednesday, Sept. 14, 1977

SEATTLE API—Veteran Bob Lurtsema and five other players were

cut from the active roster Tuesday as the Seattle Seahawks reduced their

National Football League team to the 43-player limit.

Tight ends John McMakin and Charles Waddell, running back Hugh McKinnis and cornerback Ernie Jones also were placed on irrevocable waivers Tuesday. Randy Coffield, linebacker, was placed on injured reserves with a knee injury, meaning he is out for the season.

Lurtsema, 34, an 11-year veteran, was obtained last year from the Minnesota Vikings and became a starter at defensive end. Unless he is claimed by another team, Lurtsema likely will be one of those signed to a new contract by the Seahawks when the NFL teams are allowed to sign two extra players later. The rosters will be increased lo 45, but only 43 will be permitted to suit up for the game.

Waddell was acquired in the veteran allocation last year but missed an entire season because of a knee injury. Jones and Coffield were 1976 draftees— Jones in the fifth round and Coffield in the tenth.

McMakin was waived late Tuesday after the Seahawks picked up tight end John Sawyer on waivers from the Houston Oilers. The release of McMakin leaves Seattle with only nine of the original 39 players the club selected in last year's veteran allocation.

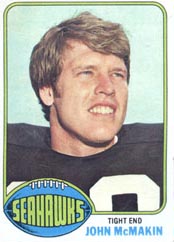

Collecting John McMakin?

1976 Topps #66