Source: Norm Evans' Seahawk Report, Vol. 4, No. 2, April 19-May 2, 1982

‘82 draft

Seattle makes room

for draft helper:

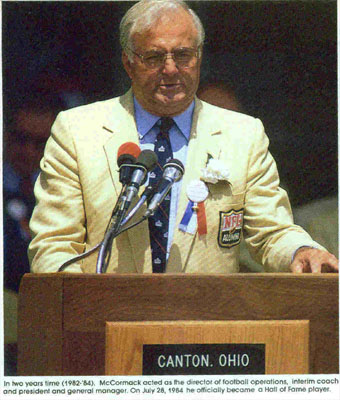

Mike McCormack

by

Chuck Niemi

It was late afternoon and the Seahawk administration complex faced a setting sun that was casting an amber glow over Lake Washington. Suddenly, a small flock of geese flew by the office windows and the man stopped in mid- sentence, obviously appreciating a new spectacle.

His previously calm, solemn tones turned animated as he exclaimed, “Now that’s something you’re just not going to see back in Baltimore.”

The only birds Mike McCormack saw in Baltimore were vultures and dodos. It wasn’t a pretty picture, but then the birds weren’t too thrilled either.

McCormack would be among the first to tell you that timing is everything. Not just in football, but

in life as well. A pair of losing seasons, including last year’s 2-14 disaster, along with same none-too- subtle bits of intervention from a president named Robert Irsay, made the timing right for a move.

For the first time since 1964 when he was selling insurance in Kansas City and moonlighting as a professional scout, Mike McCormack isn’t coaching professional football players. He is the Seahawks’ new director of football operations which, in his words, “. . . is kind of an administrative assistant to John (Thompson) and Jack (Patera).”

In Thompson’s words, “McCormack will oversee all aspects of the football operation, but will not be involved with any coaching decisions. His first duties will be to become familiar with our personnel and the college players eligible for the upcoming

draft.”

He will also direct the activities of trainers, equipment staff, game-day operations, training camp and be involved in contract negotiations.

You would have to be naive, crazy or both not to assume that his opinions will be actively solicited on any number of matters. With utmost tact, he says, “It’s just another viewpoint in the overall organization.”

McCormack succeeds current Assistant General Manager Mark Duncan whose intention it is to retire after the 1982 season. Duncan has been with Seattle since Day One, or at least April, 1975. Thompson cited Duncan’s work and background as being invaluable in the Seahawks’ early success. “His input in all phases of the operation put us ahead of where we might have been without him,” the Seattle GM noted.

McCormack is a respected figure in professional football—and is immediately likeable as well. The oft-heard tag, “a player’s coach,” seems to fit. If there is an uncertainty, or precariousness, in his new position, he has either ignored it or refused to accept it.

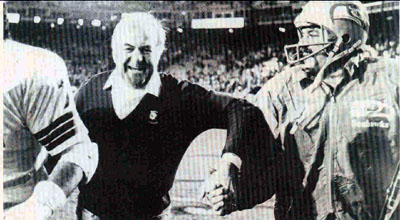

As a former head coach (Philadelphia Eagles, 1973-76; Baltimore Colts, 1980-81), his opinions were heretofore commands. His opinions now will take the form of recommendations, albeit from a highly valued and knowledgeable source. He’s sensitive to the difference, yet expects no problems. “I think I can do that,” he says. “There’s always going to be second-guessing. That’s just the nature of this business.”

One aspect of football that will be missing is the competition, and that’s no small matter for a man who played on six Pro Bowl squads and two NFL championship teams (Cleveland Browns), in addition to a long coaching career.

He laughs and admits, “That’s what I don’t know how I’ll react to being away from the competition. I’ve always said I don’t know what normal people do in the month of August.”

An administrative job has not been a life-long ambition, McCormack readily concedes.

“No, I didn’t always envision getting into administration. I would say that, over the last few years, I’d seriously given it some consideration. It began to look like a normal progression, from assistant coach to head coach to administration. But, when I started out, I just wanted to be the best assistant coach I could possibly be.”

The thing that tipped the scales in the current direction could have been two independent phone calls from a pair of highly respected figures in professional football.

“I talked to two fairly close personal friends— Don Shula and Paul Brown—and they both suggested, long before this job ever opened up, that there was a real need for people in administration with coaching expertise,” McCormack says. “They both said it was an area I should seriously consider. And, that makes you stop and think, when people you admire and respect make a suggestion like that.”

The Seattle opportunity did not provoke an automatic affirmative response. “I had some other professional coaching opportunities,” he says, “and it was a difficult decision. As I mentioned, I had been thinking about making the move. It was an opportunity and a challenge—not that coaching wasn’t a challenge—but a challenge along an avenue I’d been considering. I think timing has a lot to do with where we all go in our careers. But yes, the timing for this happened to be right.”

McCormack would obviously be a viable candidate for any head coaching job that opened up in the near future. Would he consider making such a move? “I really don’t think it’ll come up,” he says. “I’ve more or less put that question out of my mind.”

In addition to his past head coaching jobs, McCormack was also a recent offensive line coach for the Cincinnati Bengals, a somewhat surprise of a Super Bowl participant. Does Seattle remind him at allof Cincinnati, or any other team he has been with, at the Seahawks’ current stage of development?

“No, but to tell you the truth, a lot of it is because I’ve been concentrating on the college draft and I haven’t really sat down with Jack and the coaches to take a deep look into our personnel,” he says. The area of evaluating professional prospects is tricky business but it’s an area where McCormack is expected to make a contribution. Are there players out there and, if so, who are they and where are they?

“I think there are a lot of good players out there,” McCormack says. And what could one expect to get in an “ideal” draft through the first six rounds? “I think you’d be talking about getting some good offensive and defensive linemen,” he added. “There are some good linebackers available up high, and the running backs look fairly deep.

“You’re never really sure how it’s going to work out,” he continued. “Sometimes an apparently good draft choice doesn’t work Out. They, you’ll see another team gamble on a player and he surfaces to the top and you ask yourself, ‘Look what would have happened if we had taken this guy!’ Again, that’s part of the job. We have to see who has peaked out, who is on the way up, who is still improving, just hash it all out, find out as much as we can. We’ve just got to know more about more people.”

McCormack is a firm believer in personal contact with prospects. “Oh yeah,” he says, “you can gain a lot more knowledge by visiting a prospect in person, but this isn’t something new. Joe Paterno (Penn State’s highly successful coach) won’t take a player, won’t offer him a scholarship, until he’s had dinner with him and sees what the family’s values are and see how they live. He sure crams a lot of meals into a short period,” McCormack laughs, “but maybe that’s why he’s so darn successful.”

McCormack has an affection for Paterno and, in that regard, he was asked, everything else being equal, would he be more inclined to take a second look at a player coming out of a program where the head coach was a highly respected figure?

“When you look at kids from successful programs, I think you’ve got to ask yourself what makes them successful? Is it the system, or the type of player the coach gets? I mentioned Paterno. Don James is another. We’ve drafted a number of players from his program. John Robinson at USC is another. Whether you credit the coach himself, or credit him for going out and getting good players, it becomes a situation of which comes first, the chicken or the egg? But yes, those players do get second looks.”

There is a theory that one player—one great player—can turn a franchise around. McCormack will accept that theory in order to make a point.

“The framework of a football team is extremely fragile” he began. “You can get one player who can make it for you, or you can have one player destroy it. I think San Francisco getting Fred Dean (defensive end) last year is an example. They were 2-3 when he arrived. All of the sudden, he starts making some big plays for them and they get it turned around. They had gotten (Jack) Reynolds (linebacker) earlier and, while he certainly helped their defense, he wasn't the catalyst that Dean was. But, they had a lot of good players there already. I think the same thing is true here. There are a lot of

good players, but somebody is going to have to make the big plays. It might be a veteran, or it might have to be a newcomer.”

Rather than fully endorse the One Great Draft Choice theory, McCormack prefers to emphasize the importance of making great choices each year in the first four rounds. That, he notes, should be the nucleus of the team for years to come. The catch is that it takes time.

“When you finally get a team primarily made up of guys between their fourth year and ninth year, that basically is your team,” he says. “That’s the team you’re going to live with for quite some time. And that’s why your first four draft choices are so important each year.”

The differences between teams in the NFL are minimal, McCormack will tell you, and there are no more dynasties. "The draft is working exactly the way Bert Bell fully intended it to work a long time ago," he says. "You just don't see situations anymore where one team can stockpile top draft choices."

McCormack expresses no surprises whatsoever at the recent emergence of teams like Philadelphia, Cincinnati and San Francisco. He sees a common thread.

“No, I’m not surprised at all because they all had good drafts,” he notes. “Look at a team like Cincinnati and see all their top draft choices who now play in the defensive line. All those teams built up their defense, then went to work on their offense. It takes awhile, but...”

There is no question whatsoever in McCormack’s mind that it all starts with defense.

“It’s just a foregone conclusion in football,” he says. “They may try to legislate more offense into the game to entertain the fans, but the teams that win are the ones that play solid, consistent defense. Don’t misunderstand, you have to have an offense, but the offense can go up and down while a consistent defense wins.

“Like last year in Baltimore,” he continued, “in 11 games, we were behind 7-0 before our offense ever got the football. Looking back, we probably did a poor coaching job. You’re just afraid if you don’t score, the next time you get the ball you’re going to be down 14-0. All of a sudden, you start coaching different.”

But that was Baltimore and this is Seattle. New times. New teams. New dreams.

“I’m enthused by the area, I really am,” he says with a big smile. “Of course, my wife’s only been here for a long weekend, but the sun did shine her last day here.”

Now, if the house back in Baltimore would only sell...